How Many Court Cases Involve Surveillance Cameras

Abstruse

In that location has been extensive research on the value of airtight-circuit television (CCTV) for preventing criminal offence, but little on its value as an investigative tool. This study sought to establish how frequently CCTV provides useful evidence and how this is affected past circumstances, analysing 251,195 crimes recorded past British Transport Police that occurred on the British railway network betwixt 2011 and 2015. CCTV was available to investigators in 45% of cases and judged to exist useful in 29% (65% of cases in which it was available). Useful CCTV was associated with significantly increased chances of crimes being solved for all crime types except drugs/weapons possession and fraud. Images were more likely to exist available for more-serious crimes, and less probable to be available for cases occurring at unknown times or in certain types of locations. Although this research was express to offences on railways, it appears that CCTV is a powerful investigative tool for many types of crime. The usefulness of CCTV is limited by several factors, most notably the number of public areas not covered. Several recommendations for increasing the usefulness of CCTV are discussed.

Introduction

Closed-excursion tv set (CCTV) surveillance cameras are widely used in policing, but that apply is controversial. The Britain (UK) government has described CCTV as "vital" for detecting offenders (Porter 2016), while the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Constabulary Section (2007, p 2) argued that it is often "invaluable to police investigations". On the other side of the debate, the campaign group (Freedom 2016) argued that all-encompassing utilize of CCTV "poses a threat to our manner of life" and that "widespread visual surveillance may well have a chilling event on costless speech and activeness". Similarly, the American Ceremonious Liberties Marriage claimed that public CCTV surveillance creates "an almost Orwellian potential for surveillance and virtually invite[s] corruption" (Steinhardt 1999).

In the bookish literature, there has been discussion of how CCTV fits into broader conceptions of surveillance (Hier 2004; Koskela 2003) and the extent to which it increases or changes the nature of state or corporate power over citizens (Fyfe and Bannister 1996; Norris and Armstrong 1998). Concerns have been raised that CCTV surveillance may restrict the diversity and vibrancy of life in public spaces (Bannister et al. 1998), or contribute to the exclusion of some groups in society (Reeve 1998). There has also been political contend about the proper residual between ensuring the effectiveness of CCTV and protecting the privacy of citizens (Sheldon 2011).

Although the debate nigh CCTV has been both long lasting and wide ranging, empirical evidence on the topic has so-far not covered all of its aspects. This commodity will endeavour to provide bear witness to inform i area of this debate virtually which evidence is currently limited: the extent to which CCTV is valuable for criminal investigations. The side by side section contains a review of the existing literature, followed by an explanation of the mechanisms that may influence the effectiveness of surveillance cameras in investigations. The following section will describe the data used in this study, derived from police reports of crimes on the railway network of Smashing Great britain. The results department will describe how often CCTV has been useful in criminal offense investigations, and in what circumstances. Finally, the implications of these results for policy makers and practitioners will be discussed.

Existing Literature

Given the controversial nature of CCTV, surprisingly little is known virtually how it is used and how effective it is in achieving many stated aims. CCTV has several potential applications for public safe, and has been deployed with the intention variously of preventing crime, detecting offences, improving the response to emergencies, profitable in the direction of places and reducing public fear of crime (Ratcliffe 2011, p xv). CCTV tin besides be used for purposes not related to public rubber, such as monitoring send-passenger flows and investigating complaints confronting facility staff (National Rail CCTV Steering Grouping 2010, p 7).

Of these potential applications, almost all research attention to date has concentrated on the use of CCTV to prevent crime (Honovich 2008). Early studies by Mayhew et al. (1979) and Webb and Laycock (1992) suggested that CCTV was constructive at reducing robberies at London Surreptitious stations, although the evaluation methods used had some limitations. Since and so, the subject has received substantial research attention with mixed empirical results. For case, several evaluations take establish CCTV to exist constructive at reducing thefts in car parks (Poyner and Webb 1987; Tilley 1993) merely others take shown information technology to accept little or no touch on law-breaking in residential areas (Gill and Spriggs 2005). A systematic review by Welsh and Farrington (2008) of 41 studies ended that CCTV is constructive at preventing some types of criminal offence in some circumstances, but that the evidence suggests it has a more-limited touch than its widespread deployment may advise.

In contrast to the extensive literature on the value of CCTV for criminal offence prevention, there is petty research on how useful cameras are for other purposes. Ditton and Short (1998) found that in the two years later the installation of a CCTV scheme in a Scottish town, the proportion of crimes that were solved by police increased from fifty to 58%, with some offences showing larger increases than others. All the same, no data was given about whether these changes were statistically meaning, and rates were only provided for some types of crime (the primary focus of the study was on crime prevention). In Australia, Wells et al. (2006) found that monitored CCTV in 2 suburbs led to the early arrest of a small number of offenders at the scenes of crimes, merely did non wait at whether recordings were useful in the subsequent investigations.

Limited evidence can be establish in research on solvability factors: the features of an offence that determine the likelihood of the example being solved. Paine (2012) constitute CCTV to not be associated with higher detection rates for residential burglary. For non-residential break-in, Coupe and Kaur (2005) constitute that CCTV being installed in a edifice was associated with double the rate of detections compared to other buildings, driven past the increased availability of suspect descriptions. Since this report used data from the yr 2000, it is possible that subsequent developments in technology may have influenced the effectiveness of CCTV in solving this blazon of crime. For example, modern cameras are likely to provide higher-resolution images, and digital (equally compared to tape-based) storage allows images to be retained for longer (Taylor and Gill 2014). Existing research on solvability factors is express because it is largely focused on the investigation of a single criminal offence type (burglary).

In the context of this limited academic evidence, several organisations take produced reports on the topic of the value of CCTV for investigation, some of dubious quality. For example, Davenport (2007) summarised an unpublished report past the Liberal Democrat political party which concluded that CCTV cameras were ineffective but because London boroughs with more cameras did non take a higher all-law-breaking detection rate. The group appeared to take made no attempt to control for confounding variables or for different types of crime. Despite the poor quality of the analysis, this study has subsequently been cited in the media (due east.chiliad. by Bates 2008) as proof that CCTV is ineffective in investigations.

Journalists have also carried out their ain analyses. Staff from The Scotsman (2008) newspaper reported that in a iv-year period CCTV cameras in Scotland had observed more 200,000 incidents, with responding police officers making arrests in 14% of cases. However, no details were given on whether those arrests led to charges, whether further suspects were identified later or how the headline statistic varied in unlike circumstances or for unlike types of crime. In San Francisco, journalists constitute that cameras had given detectives new avenues of investigation in seven of 33 violent felonies committed in a crime hotspot over a 2-year period (Bulwa and Stannard 2007). Meanwhile the London Borough of Hackney (2016) reported that over a 12-yr period the use of CCTV had been associated with more than 27,000 arrests, although it gave no further details. Edwards (2009) reported that CCTV evidence was gathered in 86 of 90 murder investigations and was judged by senior police officers to have been valuable in 65 of those cases.

There appears to be some disagreement within the police service equally to how effective CCTV cameras are in criminal investigations. Several news outlets summarised a report from the London Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) that appeared to exist highly critical of its usefulness. Bowcott (2008) reported that "only 3% of street robberies in London were solved using CCTV images", although other articles reported that the 3% statistic applied to all crime (due east.g. Johnson 2008). In another article based on the same report, Edwards (2008) wrote that "up to 80 per cent of CCTV footage seized by police is of such poor quality that it is almost worthless for detecting crimes". Hickley (2009) quoted a law spokesperson as proverb that "in 2008 less than i,000 crimes were solved using CCTV despite there being in excess of i million cameras in London". All the same, to the nowadays author's knowledge, the written report itself remains unpublished and no information is available on the methods used, nor whatever more than details of the conclusions.

In dissimilarity, the bulk of British officers surveyed by Levesley and Martin (2005) believed that CCTV was a useful investigative tool. A study on the value of CCTV commissioned by Dyfed-Powys Police in Wales argued that cameras were valuable in the detection of crime, citing the opinions of police investigators and local prosecutors. However, the study also recommended that alive-monitoring of CCTV end because it was ineffective at preventing crime or improving the initial response to incidents (Instrom Security Consultants 2014). Several municipalities in Britain take decreased their investment in CCTV in response to recent upkeep cuts (Merrick and Duggan 2013).

Overall, petty appears to be known well-nigh how the usefulness of CCTV for investigation varies across law-breaking types or circumstances, which is probable to be of import in any attempts to make CCTV more useful. The present exploratory study attempted to provide some testify in these areas.

How Might CCTV Assist Crime Investigations?

Before turning to the enquiry questions addressed in this report, it is necessary to consider exactly how CCTV might provide useful evidence in a criminal investigation.

A criminal investigation can be thought of as a series of questions: who was involved in an incident, where did it happen, what happened, when did it happen, why did it happen and how were any offences committed, known as the '5WH' investigation model (Cook et al. 2016; Stelfox 2009). CCTV may exist useful in answering at to the lowest degree two of these questions: what happened and who was involved (La Vigne et al. 2011).

A good-quality recording could potentially allow investigators to watch an entire incident unfold in item, providing data well-nigh the sequence of events, the methods used and the entry and exit routes taken by the offender. Even if this is not possible, CCTV may exist useful in corroborating or refuting other prove of what happened, such as witness testimony (College of Policing 2014). Recordings may besides provide information that investigators can use to contextualise other evidence (Levesley and Martin 2005).

CCTV may assist in identifying who was involved in a criminal offence either direct, as when a suspect is recognised past someone viewing the recording, or indirectly, such as when the recording shows a suspect touching a surface from which police are and so able to recover forensic prove (Clan of Chief Police Officers 2011). Images tin can also be used to identify potential witnesses (La Vigne et al. 2011, p 27). CCTV may be less useful in answering some of the other 5WH questions. For example, fifty-fifty a good-quality recording may shed piddling light on why a crime was committed.

In lodge for CCTV to be useful in answering investigative questions, sure circumstances are required. There are few legal restrictions on the ability of police officers to use CCTV recordings of public places during investigations. In the UK, for example, operators of camera systems can provide recordings to the constabulary without a warrant (Information Commissioner's Role 2015). In the United States (US) a similar system operates, as long as the recording is of a identify in which people do not take a reasonable expectation of privacy (Chace 2001). As such, the limiting factors on the use of CCTV are probable to have other forms.

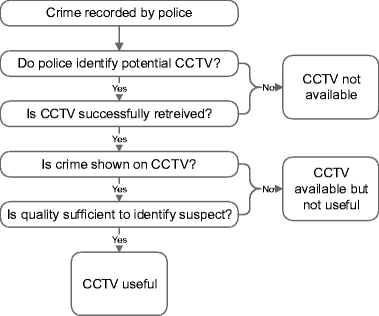

Effigy 1 summarises the process past which these circumstances may come about, broken down into three stages. In the commencement stage, CCTV show is not bachelor, either because the police have non taken steps to obtain information technology or because no recording exists for technical reasons. In the second stage, a CCTV recording is bachelor but—perhaps because of the recording quality—is non useful to the investigation. In the final stage, a recording is both available and useful to the investigation.

The process by which CCTV can be bachelor and useful to an investigation

The present study aimed to explore the usefulness of CCTV for crime investigation by examining the stages in this process. Specifically, two inquiry questions were addressed:

- 1.

How often practise CCTV cameras provide useful bear witness in criminal investigations, and how does this vary for different types of crime?

- ii.

In what circumstances is CCTV virtually likely to be useful in criminal investigations?

It might be idea that CCTV is useful in a case just if it leads to a doubtable existence bedevilled. Even so, this approach presents at to the lowest degree two issues. Firstly, it would require a potentially unreliable counterfactual test of the weight of show that would have been available in a item case in the absence of CCTV recordings. Secondly, information technology ignores the potential value of video recordings in allowing officers to eliminate a suspect from their enquiries, or to identify where a person has made a false report of crime.

Data and Methods

Answering the inquiry questions addressed in this study required a source of information on the investigative value of CCTV. Although police forces collect a wide range of information about investigations for administrative and legal purposes, that information is non e'er stored in a manner that makes information technology accessible for secondary assay for research purposes. For example, case files may incorporate data on whether CCTV recordings were used in a particular investigation, but such files are oft held either on paper or in electronic formats that are non easily searchable. Equally a event, research based on instance files (e.g. Jordan 2004; Cockbain et al. 2011) tends to use small samples, potentially limiting its power to observe differences betwixt offense types, circumstances and so on.

The present research takes advantage of one police force having collected information on the value of CCTV over a long period of time and stored information technology in an attainable format. In 2010, British Transport Police (BTP)—the specialist police force for railways in Groovy Great britain—added 2 questions to the electronic form that first-line supervisors are required to complete at the finish of a criminal investigation conducted by an officer under their control. The get-go question asks the supervisor whether CCTV has been useful in the investigation and the second (required only if the answer to the first question is 'no') asks the supervisor to choose from a list of reasons why CCTV has non been useful in that case. From these 2 questions it is possible to construct a third variable showing whether a CCTV recording existed in a instance, past combining those cases where CCTV was useful with those where a recording of the location at the relevant time did exist but was not useful (for case because the images were of insufficient quality or considering the incorrect images were extracted from the organisation).

The nowadays study used the answers to these questions together with other data about each offence, such as whether a example had been 'solved'. In mutual with standard practise amid United kingdom law forces, crimes were deemed to exist solved if a prosecutor (or, in minor cases, a peculiarly trained police officer) decided that there was sufficient evidence against a suspect to ship the case to courtroom. Again in common with police practice, such cases are referred to below as having been 'detected' (for further details, encounter Home Office 2016).

In the v years between January 2011 and Dec 2015, 251,195 notifiable crimes were recorded by BTP, or about 138 crimes each twenty-four hours. Footnote 1 Since the data on CCTV usefulness is gathered simply at the conclusion of an investigation, information for this written report were extracted from the BTP law-breaking-recording system at the starting time of March 2016 to maximise the gamble of the relevant questions having been completed. Data on the usefulness of CCTV were missing in four,768 cases (1.9% of the total).

The utilise of data from BTP was valuable for two reasons. Firstly, that force had for several years been collecting data that were not widely recorded elsewhere, providing a big sample of offences to study. Secondly, the railway network policed past BTP has a very large number of CCTV cameras. The total number of cameras on the railway network is non known, since the 25 railroad train operating companies each operate their own photographic camera networks and in that location is no central registry of cameras. Notwithstanding, the BTP CCTV Hub is able to monitor around 30,000 cameras at railway stations effectually the state (British Transport Police 2016). In that location are also an unknown number of cameras installed on-board trains.

The big number of cameras means that CCTV volition cover the sites of a substantial proportion of recorded crimes. This helps to deal with a potential limitation of the studies discussed above, which is that only a few of the offences reported to those forces are likely to accept occurred close to a CCTV camera. This in turn would make it more than difficult to reply the 2d research question.

While the availability of data from BTP fabricated this written report possible, the utilize of information from a specialist constabulary force may limit the generalisability of the results. The mix of crimes investigated by BTP is probable to be different from that seen by local police forces.

Another limitation of this data source is that in cases where supervisors identified that CCTV had been useful in an investigation, it was not possible to identify in what way it had been useful. This is a limitation of the data collection, which in plow is probable to reverberate a focus within the constabulary on improving CCTV usefulness by focusing on the reasons why recordings were sometimes not useful. It is probable that supervisors classified cases with reasonable consistency, since the 2d question described higher up asked them to pick from a list of reasons (shown in Table 1) why recordings were non useful. Consistency is besides likely to have been maintained by the questions asked of supervisors beingness constant over fourth dimension. Nevertheless, information technology is not possible to be certain that supervisors categorised cases with complete consistency. Neither can the possibility of bias be excluded, although the author is aware of no obvious sources of bias.

The data did non distinguish between different types of CCTV. Systems can vary from extensive loftier-definition networks to single cameras that produce grainy images (Gill and Spriggs 2005; Taylor and Gill 2014). It is therefore likely that the effectiveness of systems will vary. Information about organization type was not recorded in the BTP data and so it was not possible to explore these distinctions. Even so, there may exist less variation in systems on railways compared to systems in other environments, considering there are industry standards for rail CCTV networks (National Rail CCTV Steering Group 2010).

Despite these limitations, to the writer's knowledge the sample used here represents the best-available large-scale dataset on the value of CCTV for investigating crime. More-detailed data could have been nerveless for a smaller sample of crimes (for example by interviewing investigators or reviewing case files), merely it would have been impractical to practise this for a big-enough sample to let assay of different crime types and crimes occurring in dissimilar circumstances.

Results

How often is CCTV Useful?

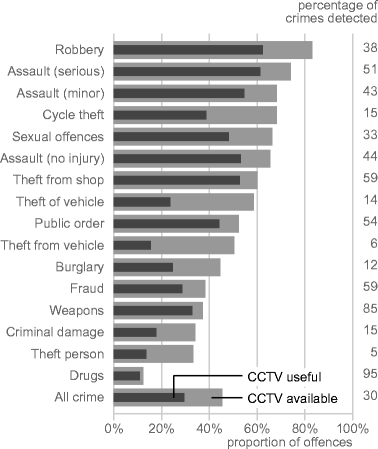

Using the distinction between availability and usefulness shown in Fig. 1, CCTV was available in the investigation of 111,608 offences in the 5 years between 2011 and 2015—45.3% of all crimes recorded by BTP. CCTV was classified as being useful in 72,390 investigations—29.4% of all recorded crimes and 64.9% of crimes for which CCTV was available. Camera recordings were, for example, useful in the investigation of 1,223 assaults causing serious injury, four,120 assaults causing small-scale injury, 1,365 personal robberies and two,810 sexual offences. Table 1 provides further details.

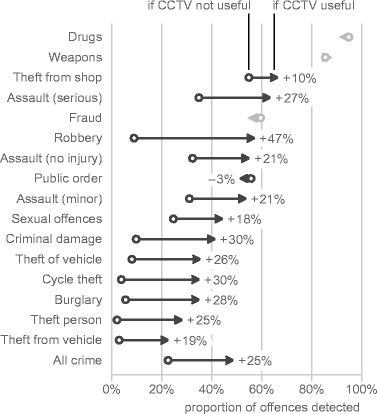

Figure ii shows the proportion of offences of dissimilar types for which CCTV was available and, within that, the proportion for which it was useful. In that location are large variations across crime types, with recordings being useful in 62.ii% of robbery investigations but only 10.seven% of drug investigations. There was also variation in the proportion of cases where CCTV is useful given that information technology is available: recordings were often available in cases of thefts from motor vehicles, just are frequently not useful; in drugs cases, images were rarely available but (when they were) they were almost-always useful. Effigy iii shows the detection rate for offences of each type in which at that place was or was not useful CCTV prove. Where the difference is meaning at p < 0.001 using a chi-squared test, the percentage-point difference is shown. Footnote 2

Proportion of crimes for which CCTV recordings were useful in the investigation

Probability of criminal offence existence solved if CCTV is useful or is not. Percentage difference is shown if pregnant at p < 0.001

Having useful CCTV show is associated with a significantly increased detection rate for all types of crime except drugs, fraud and public social club. The largest change is for robbery, where the probability of detecting an offence increases from 8.9% without useful CCTV to 55.7% with information technology. Absent CCTV, detection rates for avaricious crimes are very low (< x%): but 2% of theft from the person offences are detected if no CCTV is available. For all types of acquisitive crime (except shop theft) useful CCTV evidence is associated with an increase in detection rates of at to the lowest degree 19 percentage points.

Detection rates in the absence of useful CCTV are higher for tearing crimes than for acquisitive crimes. This may exist because for fierce offences there is ever at least one witness (the victim) present at the scene. However, the existence of useful CCTV remains associated with significantly college detection rates for all types of assault, and for sexual offences.

CCTV is only rarely useful in the investigation of drug or weapon offences (Fig. 2) and the proportion of those offences that are detected is not significantly different when CCTV is or is not available (Fig. 3). This may be because such offences are "intangible" (Chappell and Walsh 1974, p 494): they typically only get known to the police when officers discover them through pro-agile tactics such every bit finish and search. In such circumstances it is unlikely that officers will need CCTV, since the discovery that an offence has occurred also provides the prove needed to solve it. Put another way, these crimes may exist likely to be "self solving", in that the identity of the perpetrator is obvious from an early phase in the investigation (Innes 2007, p 257).

Unlike other types of theft, detection rates for shoplifting are relatively high in the absenteeism of useful CCTV, which is only associated with a modest increase in detection charge per unit. This may suggest that tangibility is not a binary state. Shoplifting offences are known to be essentially nether-reported to the police (Home Office 2014), with some shopkeepers often just reporting offences when the thief has been caught, while others written report all incidents of which they are aware. As such, shoplifting may be a 'semi-tangible' offence.

No significant association betwixt CCTV usefulness and detection rates was establish for fraud offences, just this may be for a different reason. While fraud can take many different forms, information technology is often an offence where physical activeness is less important than the offender's intentions. As such, visual evidence such as that provided by CCTV may be less likely to be useful.

Overall it appears that CCTV is frequently useful in investigating a broad range of crimes, although its usefulness varies substantially betwixt criminal offence types. However, it is important to note that it is not possible to plant causation in non-experimental studies such equally this. The assay presented so far as well does not accept into account other variables that may explain the clan between CCTV and criminal offence detections. This is the focus of the post-obit sections.

In What Circumstances is CCTV Most Probable to be Useful?

Based on the results presented in the previous section, five hypotheses were adult nearly the circumstances in which CCTV is virtually likely to be (a) available and (b) useful. Given that usefulness is dependent upon availability, the process by which CCTV might be useful was modelled in 2 stages. The first modelled whether or not a CCTV recording is available and the second modelled whether, if a recording is available, it would be useful or not. Split binary logistic regressions were run for these two stages, with the aforementioned predictors used in both models.

The showtime hypothesis was that:

H1: the availability and usefulness of CCTV will depend upon the type of criminal offence being investigated.

This hypothesis was based on the results shown in Figs. 2 and iii, and was included to ensure that variations in availability or usefulness past crime type were controlled for in the model.

Some offences are "aoristic" (Ratcliffe and McCullagh 1998), in that the time at which they occur is not known precisely. Instead, the constabulary typically merely know the showtime and last possible times at which the crime occurred, such every bit the time a victim left their car unattended and the time at which they returned to find it had been stolen (Ashby and Bowers 2012). The window of opportunity between these two points expresses the period over which the offence could take occurred. A related consequence for transport crime is that offences can occur between two locations (such every bit a bag stolen at an unknown betoken during a train journey), which Newton et al. (2014) referred to as "interstitial" offences.

If the aoristic window is long, it is possible that the investigating officeholder will be less probable to asking or view CCTV. For case, if a pocketbook is stolen from a auto that has been left unattended for a week, the officer may decide non to seize recordings from any cameras in the area because viewing such a large volume of textile would be unfeasible. Every bit such information technology was hypothesised that:

H2: the longer the window of opportunity in which a crime could accept occurred, the less likely it will be that CCTV will exist available or useful.

In the present data, the aoristic window was less than x minutes in 54.0% of crimes, betwixt x minutes and 1 60 minutes in 19.4%, between 1 and 24 hours in 20.two% and greater than 24 hours in vi.four% (median = 6 minutes, inter-quartile range = 81 minutes). Since this variable was skewed, it was transformed using a natural logarithm before inclusion in the models.

As discussed in a higher place, some types of law-breaking (such every bit drug possession) are often detected very chop-chop because they are self solving. This may also exist the case where the evidence is overwhelming, or where the suspect rapidly admits the offence. In such circumstances the investigating officeholder may decide that retrieving CCTV is not necessary, and and then any recording volition not be useful to the investigation, whether or non if information technology exists. As such:

H3: CCTV will be less likely to be bachelor or useful in cases that are detected chop-chop.

To exam this hypothesis, offences were categorised according to whether or not they were detected within 72 hours of occurring, equally was the instance in nine.ix% of crimes.

The value of CCTV may vary according to the blazon of location at which the offence occurred. For instance, offences occurring at the side of railway lines may exist less probable to produce useful CCTV than offences in station ticket halls. To business relationship for this:

H4: The availability and usefulness of CCTV will depend upon the type of place in which the offence occurred.

Offences were categorised (based on a variable recorded past BTP) as occurring either at stations (37%), onboard trains (33% of offences), on or alongside railway lines (vii%), in car parks (4%) or at other locations (19%).

Information technology is unlikely that all types of crime will be equally important to investigators. I reason why officers may prioritise particular investigations (and therefore exist more than likely to identify CCTV show) is that they involve crimes that are believed to be particularly serious because of their impact on individuals or society. As such:

H5: The more than serious that a criminal offence is, the more likely it will be that CCTV will exist bachelor and useful.

Operationalising the severity of individual crimes is problematic, since damage comes in many forms. One method that has been discussed in recent literature is to employ the severity of penalisation expected for a particular offence as a proxy for the harm caused by it (encounter, for instance, Sherman 2013; Ratcliffe 2014). More specifically, sentencing guidelines can be used to determine the number of days in prison likely to be imposed on a kickoff-time offender before any aggravating or mitigating factors are taken into consideration. For the nowadays report, these starting-point sentences were obtained from the Magistrates' Court Sentencing Guidelines (Sentencing Guidelines Council 2008). Following (Sherman et al. 2016), in cases in which the starting point was a community penalty (which is typically specified equally a number of hours of, for example, unpaid work) this was converted to days imprisonment based on an viii-hour working day.

Current sentencing guidelines in England and Wales set monetary penalties based on an offender's weekly income (run into Sentencing Guidelines Council 2008, p 148), then fines were converted to days of imprisonment based on how long it would have taken for an offender to earn the coin to pay the fine. For example, the starting-point sentence for cannabis possession is a fine equal to 100% of the offender's weekly earnings. Given a five-day working week, for the purposes of severity this could be converted to five days of imprisonment, since that is for how long the offender would take to piece of work to earn that coin.

In one case a judgement had been converted to days of imprisonment, the variable was scaled to 28-mean solar day periods of imprisonment to give a range of values that could be interpreted more easily. The median severity, expressed as the equivalent months in prison, was 1.0 months, with an inter-quartile range of 0.74 months. Nevertheless, some offences had much higher values: 195 months (16 years) for murder and 130 months (11 years) for rape of a child. Since this variable was skewed, it was transformed using a natural logarithm.

Table ii shows the results of a binary logistic regression model with the availability of CCTV every bit the dependant variable, based on 250,665 cases. For each variable, the tabular array shows the estimate (β), the standard error (SE) and associated p value, the odds ratio (e β ) and the estimated percent change associated with a one-unit of measurement increase in the value of each predictor (e β − one). Table 3 shows the same information for the model used to predict whether CCTV would exist useful in cases in which it was available, based on 111,344 cases. Footnote three

Overall, compared to a zip model with no predictors, the models were significantly better at predicting whether CCTV would be bachelor (χ 2(xix) = 44,206, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R ii = 0.22) and—if so—whether information technology would be useful (χ 2(19) = 18,465, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R ii = 0.21). Generalised variance inflation factors (used because some predictors were non binary) were less than ii.4 for all the predictors, suggesting no concerns about multi-collinearity.

As discussed in the previous section, the likelihood of CCTV existence both bachelor and useful varied between dissimilar types of crime, in line with the prediction of H1. For intangible offences such as the possession and supply of drugs or weapons, CCTV was less likely to exist available than for other offences. However, if a recording was available then it was much more probable to be useful. Conversely, recordings were more likely to be available in investigations of thefts of or from vehicles or pedal cycles only (when available) were less likely to exist useful. This is interesting considering it is for offences in car parks that the criminal offence-prevention benefits of CCTV have been most often demonstrated (Welsh and Farrington 2008). The nowadays finding may exist because vehicle and cycle thefts are typically not interstitial, and and then it is easy for officers to identify what CCTV recordings to obtain. Notwithstanding, such offences ordinarily are aoristic (Ashby and Bowers 2012), so information technology may exist hard to obtain useful testify from the recording when it is viewed considering of the difficulty of identifying an offender (or fifty-fifty an offence occurring) among many hours of recordings.

The circumstances of the offence were meaning predictors of both availability and usefulness. The greater the window of time of which an offence could have occurred, the less likely CCTV was to be bachelor and (when available) to be useful, in accordance with the prediction of H2.

CCTV was simply half as likely to be available in cases that were detected within 3 days of existence reported as in those that were non, supporting the prediction of H3. However, in quickly detected cases for which CCTV was available, it was more four times as likely to be useful every bit in cases that were not detected quickly, contrary to the prediction.

In accordance with H4, the type of place in which an offence occurred was a meaning predictor of both the availability and usefulness of CCTV. Compared to offences that occurred in stations, recordings were less likely to be available for offences occurring at the side of railway lines or on trains. This almost certainly reflects the distribution of cameras, since CCTV equipment is ubiquitous in stations just not and then forth the many thousands of kilometres of track. Fewer cameras may also hateful less overlap betwixt the areas covered by each camera, and and then a greater likelihood that an area will be covered only at the periphery of a photographic camera's coverage. This may explain why CCTV is less likely to exist useful at the line side even when information technology is bachelor.

While cameras are condign common in trains, recordings are often kept for a shorter period than in other types of CCTV system (National Rail CCTV Steering Group 2010), meaning that whatsoever filibuster in requesting images from a train-operating company may mean that on-train images have been overwritten when this would not be the instance if the offence had happened in a station. Lack of cameras cannot, however, explain the credible lower availability of recordings for offences in automobile parks, since CCTV has long been used in such locations (Poyner and Webb 1987).

Every bit predicted past H5, the more serious an offence, the more than likely it was that CCTV would be available to officers. There are several potential reasons for this. Firstly, the operators of CCTV systems may take developed them with their utilise confronting serious crimes particularly in mind. For example banks have for many years deployed CCTV systems effectually automatic teller machines (ATMs) to combat robbery of customers (Scott 2001). Secondly, victims may have been more probable to study more-serious offences promptly, making it more likely that recordings would be available to officers. Thirdly, investigating officers may exist more probable to invest the time and effort required to obtain and view CCTV in more-serious cases. In any case, where CCTV was available, seriousness was not associated with any change in the likelihood of the recording being useful.

The factors considered in this department suggest that CCTV is more useful in sure circumstances than in others. However, the Nagelkerke R 2 values for the models (R 2 = 0.22 for availability and R two = 0.21 for usefulness) propose that there is substantial variation in the availability and usefulness of CCTV that is non associated with these factors.

Discussion

This study produced several potentially useful findings. Firstly, CCTV is ofttimes useful in the investigation of crime (Fig. 2): recordings were useful in an average of 14,478 BTP investigations a year, including 3,363 assaults, 2,378 vehicle thefts, 562 sexual offences and 273 robberies. The availability of CCTV was associated with substantial increases in the likelihood of nigh types of offences being solved, with some types of crime very unlikely to be solved when CCTV was not available (Fig. 3).

Secondly, a number of situational factors announced to be associated with the likelihood of CCTV being available and (if so) useful. Recordings were less probable to be bachelor for offences occurring in locations such every bit on trains or (in particular) at the side of the rail (Table 2). CCTV was also less likely to be available if an offence occurred during a long window of opportunity. In cases in which recordings were available, they were less probable to be useful for offences in car parks or involving thefts from the person (Table three).

Thirdly, information technology appears that the apparent low usefulness of CCTV reported in previous studies such as the unpublished study produced past the MPS may exist a function of CCTV being but infrequently available to some investigators. The present study was able to distinguish betwixt the availability and usefulness of CCTV, in contrast to other work that has non made that distinction, artificially lowering the apparent usefulness of camera systems. Declining to make this distinction is somewhat alike to proverb that witness show is non helpful in cases where no witnesses were present: true, but non specially insightful. In brusque, it may be that if CCTV is non often useful that is because the area in question does not have much CCTV. Future studies on this topic should distinguish between the availability and usefulness of CCTV to take this issue into account.

These findings suggest several recommendations for practice. The most important is that if CCTV is made available to investigators then it is probable to be useful in a substantial proportion of cases. At to the lowest degree in the example of railway crime, CCTV appears to be a powerful investigative tool, particularly for more-serious crimes.

This does not hateful, still, that identify managers should necessarily install CCTV cameras in all types of place, since several other considerations are relevant. Firstly, it may non be possible to replicate the extremely high density of cameras constitute in many parts of the railway environment. The cost of CCTV systems has reduced over fourth dimension, only in some cases the investment may non be justified. This is likely to be particularly truthful where the probability of a criminal offense occurring is depression. Lack of data on the location and blazon of cameras installed meant that this study was not able to consider the costs of CCTV systems, but this is likely to exist a relevant consideration for any potential system operator. Installation may be more likely to be justified where the chances of a criminal offence occurring are high (especially if those crimes are probable to be serious or very frequent), or where CCTV images can be used for multiple purposes. For case, in many railway CCTV systems images are monitored in real fourth dimension to facilitate oversupply management, with any investigative benefit being secondary to their primary purpose of public safety (a diffusion of benefit). In other circumstances information technology may exist that other interventions are likely to be more effective than CCTV in assisting investigations, or preventing crimes from happening in the first place (Ratcliffe 2011, p 21).

The present findings too suggest ways in which investigators could make ameliorate employ of CCTV. In particular, the findings point to the importance of officers identifying potential sources of CCTV images whenever possible. While officers were more likely to asking CCTV in more than-serious cases (Table ii), the likelihood of available images beingness useful was non associated with the degree of seriousness (Table iii). This suggests that if officers are able to seize CCTV in less-serious cases, they are as probable to be useful every bit in more than-serious cases. This accords with previous enquiry past Roman et al. (2008) showing that Deoxyribonucleic acid bear witness is valuable in investigations of loftier-book, less-serious offences besides as in the investigation of major law-breaking, simply that despite this officers often only expect for it in serious cases.

At that place volition sometimes exist good reasons why CCTV is non requested in a detail case, for case if the police have already obtained overwhelming evidence from other sources. Nonetheless, it is possible that there remain cases where CCTV could have been useful only in which the investigating officer did not make a request for it. A recent minor report of newly installed cameras in two violent-crime hotspots in Stockholm found that investigators requested CCTV recordings in only 20% of cases in which they were available (Marklund and Holmberg 2015). It is crucial that officers take reasonable and proportionate steps to place CCTV evidence in every case in which it may be available.

The generalisability of the nowadays results may be express by the specific characteristics of the railway environment. For example, it is unlikely that many police force agencies could achieve widespread CCTV coverage of streets and other public areas to the same caste of saturation that is experienced on railway networks in the UK. Specifications for installing new or upgraded railway CCTV systems in United kingdom recommend that at least xc% of areas such as platforms, ticket halls and car parks are covered by cameras (National Rail CCTV Steering Group 2010, p eleven). In dissimilarity, many non-railway CCTV systems cover only parts of a local area. CCTV is also probable to be useful less-often for offences that typically take identify where cameras are rarely nowadays, such as private dwellings. Even in dwellings, nevertheless, in that location have been examples of CCTV providing effective evidence after beingness installed to protect particularly vulnerable people (e.thou. Phillips 1999).

BTP investigators also do good from about railway cameras existence operated by a small-scale number of rail companies. In contrast, local police may take to place CCTV recordings that could exist held past a large number of public and individual organisations. Retrieving recordings in such cases may be both more than difficult and more time-consuming. In item, the lack of a national annals of CCTV systems may mean that officers investigating an offence in a street may have to speak to every property owner in the surface area to make up one's mind whether they operate a camera system or not.

The information used in this written report could not be used to identify whether CCTV made the difference betwixt an offence beingness detected and not being detected. It is likewise not possible to decide the nature of causality in the relationships described here without an experimental written report. Nevertheless, this study represents the most-detailed published analysis of the value of CCTV in criminal investigations.

Further research in this field would exist valuable, particularly given the scarcity of evidence on the use of CCTV for investigation. While the lack of existing enquiry means that there are many potential avenues for investigation, the present results suggest some questions that could usefully be prioritised. Firstly, when CCTV is useful in investigations, what is the machinery by which information technology acts? Identifying how CCTV works would be useful if it allowed investigators to prioritise the search for CCTV in certain types of case, or allowed researchers to identify potential barriers to constructive use of CCTV that could not exist constitute using the nowadays data. Secondly, information technology appears that investigators do non asking CCTV recordings in some cases in which they could be potentially useful. Why does this happen and what can exist done to facilitate the acquisition of CCTV evidence whenever practicable? This information would aid to remove whatsoever barriers to ensuring the availability of recordings. Thirdly, why is CCTV not useful in cases where it is bachelor? Fourthly, what tin exist done to minimise the number of cases in which CCTV is bachelor but proves not to be useful? Amend understanding of the reasons for this could assistance to ameliorate the evidence bachelor to investigators.

Notes

-

In England and Wales, constabulary forces are required to notify the Home Office of how many crimes occur of each blazon. However, very pocket-sized offences—such as failing to finish at a red traffic light or travelling on a train without a ticket—are excluded from this requirement. All other offences are included and so are referred to as 'notifiable' offences. For farther details, encounter Home Part (2011). Crime statistics and almost all research on crime in England and Wales are based on notifiable-crime data.

-

Results for the chi-squared tests are not shown for reasons of space, just are available from the writer on request.

-

To produce a model with a manageable number of variables, different types of assault and of vehicle-related theft were combined into a single category in each instance.

References

-

Ashby, Chiliad.P.J., & Bowers, G.J. (2012). A comparison of methods for temporal assay of aoristic criminal offense. Criminal offense Science, 2(1), doi:ten.1186/2193-7680-2-1.

-

Association of Chief Police Officers (2011). Exercise Advice on the Use of CCTV in Criminal Investigations. Wyboston Lakes: National Policing Improvement Bureau.

-

Bannister, J., Fyfe, N.R., & Kearns. A (1998). Closed excursion goggle box and the urban center. In Norris, C., Moran, J., & Armstrong, G. (Eds.) Surveillance, closed circuit television and social control (pp. 21–39). Aldershot: Ashgate.

-

Bates, D. (2008, May 6). Billions spent on CCTV have failed to cut crime and led to an 'utter fiasco', says Scotland Yard surveillance principal. Daily Mail.

-

Bowcott, O. (2008, May 6). CCTV smash has failed to slash law-breaking, say police. The Guardian.

-

British Transport Law (2016). CCTV. Retrieved April 17, 2016, from http://world wide web.btp.police.uk/advice_and_info/how_we_tackle_crime/cctv.aspx.

-

Bulwa, D., & Stannard, M.B. (2007, August 17). Is it worth the cost? San Francisco Relate.

-

Chace, R.Due west. (2001). An overview on the guidelines for closed circuit television (CCTV) for public rubber and community policing. Alexandria: VA: Security Industry Association.

-

Chappell, D., & Walsh, Grand. (1974). Receiving stolen property: The demand for systematic inquiry into the fencing process. Criminology, 11(4), 484–497. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1974.tb00609.x.

-

Cockbain, E., Brayley, H., & Laycock, Chiliad. (2011). Exploring internal child sex trafficking networks using social network analysis. Policing, 5(2), 144–57. doi:10.1093/police/par025.

-

College of Policing (2014). Authorised Professional person Practice: Investigation. Retrieved from https://www.app.college.police.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/app-content/investigations/investigative-strategies/passive-information-generators/.

-

Cook, T., Hibbitt, S., & Hill, Thousand. (2016). Blackstone'due south Criminal offence Investigators' Handbook, second edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Coupe, T., & Kaur, S. (2005). The Role of Alarms and CCTV in Detecting Not-residential Burglary. Security Journal, 18(two), 53–72. doi:10.1057/palgrave.sj.8340198.

-

Davenport, J. (2007, September xix). Tens of thousands of CCTV cameras, yet lxxx% of criminal offense unsolved. Evening Standard.

-

Ditton, J., & Brusque, E. (1998). Evaluating Scotland's first boondocks centre CCTV scheme. In C. Norris, J. Moran & Chiliad. Armstrong (Eds.) Surveillance, closed circuit television and social control, (pp. 155–173). Aldershot: Ashgate.

-

Edwards, R. (2008, May 6). Law say CCTV is an 'utter fiasco'. The Telegraph.

-

Edwards, R. (2009, January 1). Seven of 10 murders solved by CCTV. The Telegraph.

-

Fyfe, N.R., & Bannister, J. (1996). City watching: airtight circuit television surveillance in public spaces. Surface area, 28(1), 37–46.

-

Gill, 1000., & Spriggs, A. (2005). Assessing the affect of CCTV. Domicile Office Research Written report series. London: Domicile Office.

-

Hickley, M. (2009, August 25). CCTV helps solve but ane offense per 1,000 every bit officers fail to use picture equally evidence. Daily Mail.

-

Hier, S.P. (2004). Risky space and dangerous faces: urban surveillance, social disorder and CCTV. Social and Legal Studies, 13(4), 541–554. doi:10.1177/0964663904047333.

-

Home Office. (2011). User guide to Habitation Role offense statistics. London: Domicile Office.

-

Dwelling house Office (2014). Crimes Against Businesses Findings 2014. Retrieved from https://www.gov.united kingdom/authorities/publications/crime-against-businesses-findings-from-the-2014-commercial-victimisation-survey/crimes-against-businesses-findings-2014.

-

Domicile Office (2016). Retrieved Apr 18, 2016, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/counting-rules-for-recorded-crime.

-

Honovich, J. (2008). Is Public CCTV Effective? Retrieved April 15, 2016, from http://ipvm.com/reports/is-public-cctv-constructive.

-

Information Commissioner's Function (2015). Using the Criminal offense and Taxation Exemptions, Information Commissioner's Part, London. Retrieved from https://ico.org.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/media/for-organisations/documents/1594/section-29.pdf.

-

Innes, M. (2007). Investigation order and major crime inquiries. In Newburn, T., Williamson, T., & Wright, A. (Eds.), Handbook of Criminal Investigation (pp. 255–276). Cullompton: Devon: Willan.

-

Instrom Security Consultants (2014). Review of CCTV provision within the Dyfed-Powys Police area. Newport Pagnell: Instrom Security Consultants.

-

Johnson, M.A. (2008). Smiling! More and more than, you're on camera. Retrieved Apr sixteen, 2016, from http://world wide web.nbcnews.com/id/25355673/ns/us_news/t/smile-more-more-youre-camera/.

-

Hashemite kingdom of jordan, J. (2004). Across Conventionalities?: Police, Rape and Women'south Credibility. Criminology and Criminal Justice, four(one), 29–59.

-

Koskela, H. (2003). 'Cam era'—the gimmicky urban Panopticon. Surveillance and Guild, 1(three), 292–313.

-

La Vigne, N.Thousand., Lowry, Due south.S., Dwyer, A.M., & Markman, J.A. (2011). Using Public Surveillance Systems for Law-breaking Control and Prevention: a practical guide for law enforcement and their municipal partners. Washington: DC: The Urban Institute.

-

Levesley, T., & Martin, A. (2005). Police attitudes to and use of CCTV. Home Office Online Written report series. London: Home Part.

-

Liberty (2016). CCTV and ANPR. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from https://www.freedom-human being-rights.org.uk/human-rights/privacy/cctv-and-anpr.

-

London Borough of Hackney (2016). Hackney's improved CCTV control centre officially reopens. Retrieved Apr 17, 2016, from http://news.hackney.gov.uk/hackneys-improved-cctv-command-center-officially-reopens.

-

Marklund, F., & Holmberg, Due south. (2015). Kameraövervakning på Stureplan och Medborgarplatsen. Rapport serial. Stockholm: Swedish National Quango for Crime Prevention.

-

Mayhew, P., Clarke, R.V., Burrows, J.N., Hough, J.Grand., & Winchester, Due south.West.C. (1979). Crime in public view. Habitation Office Research Studies series. London: Home Function.

-

Merrick, J., & Duggan, Due east. (2013). Sentry out—fewer CCTV cameras about. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/great britain/home-news/sentinel-out-fewer-cctv-cameras-about-8527928.html.

-

Metropolitan Police Department. (2007). Closed circuit telly (CCTV) 2007 annual report. Washington: DC: Metropolitan Police force Section.

-

National Rails CCTV Steering Grouping. (2010). National rails and undercover closed circuit television (CCTV) guidance document. London: Association of Train Operating Companies.

-

Newton, A.D., Partridge, H., & Gill, A. (2014). Above and below: measuring crime take chances in and around surreptitious mass transit systems. Criminal offense Science, three(ane), 1–14. doi:x.1186/2193-7680-3-1.

-

Norris, C., & Armstrong, G. (1998). Introduction: power and vision. In Norris, C., Moran, J., & Armstrong, Yard. (Eds.), Surveillance, Closed Circuit Television and Social Control (pp. 3–18). Aldershot: Ashgate.

-

Paine, C. (2012). Solvability Factors in Dwelling Burglaries in Thames Valley. Cambridge: Master's thesis, Academy of Cambridge.

-

Phillips, C. Painter, One thousand., & Tilley, N. (Eds.) (1999). A review of CCTV evaluations: crime reduction furnishings and attitudes towards its utilise.

-

Porter, T. (2016). Surveillance Camera Commissioner's IFSEC speech. Retrieved from https://www.gov.united kingdom/government/speeches/surveillance-camera-commissioners-ifsec-spoken communication.

-

Poyner, B., & Webb, B. (1987). Successful Crime Prevention Instance Studies. London: The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations.

-

Ratcliffe, J.H. (2011). Video surveillance of public places. Problem-Oriented Guides for Police Response Guides Series. Washington: DC: Center for Problem-Oriented Policing.

-

Ratcliffe, J.H. (2014). Towards an index for impairment-focused policing. Policing, 9 (2), 164–182. doi:10.1093/police/pau032.

-

Ratcliffe, J.H., & McCullagh, M.J. (1998). Aoristic crime analysis. International Journal of Geographical Informatics, 12(seven), 751–764. doi:10.1080/136588198241644.

-

Reeve, A. (1998). The panopticisation of shopping: CCTV and leisure consumption. In Norris, C., Moran, J., & Armstrong, M. (Eds.), Surveillance, closed excursion goggle box and social control (Chap. iv, pp. 69–87). Aldershot: Ashgate.

-

Roman, J., Reid, Southward., Reid, J., Chalfin, A., Adams, W., & Knight, C. (2008). The Deoxyribonucleic acid field experiment: Toll-effectiveness analysis of the use of DNA in the investigation of high-book crimes. Washington: DC: Urban Constitute.

-

Scott, M.S. (2001). Robbery at automated teller machines. Trouble-Oriented Guides for Police Problem-Specific Guides Series. Washington: DC: US Section of Justice.

-

Sentencing Guidelines Council. (2008). Magistrates' court sentencing guidelines: definitive guideline. Sentencing Guidelines Council: London.

-

Sheldon, B. (2011). Camera surveillance within the Uk: enhancing public prophylactic or a social threat?. International Review of Police, Computers and Technology, 25(three), 193–203.

-

Sherman, L.W. (2013). The rise of prove-based policing: targeting, testing, and tracking. Crime and Justice, 42(1), 377–451. doi:10.1086/670819.

-

Sherman, L.W., Neyroud, P., & Neyroud, E. (2016). The Cambridge Crime Impairment Index (CHI): measuring total harm from crime based on sentencing guidelines. Policing, one–17. doi:10.1093/police/paw003.

-

Steinhardt, B. (1999). Law enforcement should back up privacy laws for public video surveillance. Retrieved April xvi, 2016, from https://www.aclu.org/accost-video-surveillance-aclus-barry-steinhardt-international-association-law-chiefs.

-

Stelfox, P. (2009). Criminal investigation: an introduction to principles and practice. Abingdon: Willan.

-

Taylor, T., & Gill, K. (2014). CCTV: reflections on its use, abuse and effectiveness. In Gill, M. (Ed.), The handbook of security (Chap. 31, pp. 705–726). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-i-349-67284-431.

-

The Scotsman (2008, May 28). CCTV: does it actually work? The Scotsman.

-

Tilley, Due north. (1993). Understanding motorcar parks, crime and CCTV: evaluation lessons from safer cities. Crime Prevention Unit Papers serial. London: Abode Office.

-

Webb, B., & Laycock, Thou. (1992). Reducing offense on the London Underground: an evaluation of 3 pilot projects. Crime Prevention Unit Papers series. London: Home Function.

-

Wells, H.A., Allard, T., & Wilson, P. (2006). Crime and CCTV in Commonwealth of australia: agreement the relationship. Humanities and Social Sciences Papers series. Golden Goast: Bond Academy. Retrieved from http://epublications.bond.edu.au/hsspubs/lxx/.

-

Welsh, B.C., & Farrington, D.P. (2008). Effects of airtight circuit television surveillance on crime. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 4 (17). doi:10.4073/csr.2008.17.

Acknowledgments

Give thanks you to British Send Police in particular Ashley Auger, Rhys Gambold,Will Jordan and Vanita Patel for providing the data used in this research. Although relevant BTP officers were given advanced access to the results of this study, control of the content and responsibleness for any mistakes lay solely with the author. Give thanks y'all also to Manne Gerell of Malm¨o Academy for providing a summary translation of a Swedish-language report by Marklund and Holmberg (2015), and to Rebecca Thompson, Andromachi Tseloni and two anonymous reviewers for commen ts on an earlier draft. This enquiry did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-turn a profit sectors

Writer information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and point if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ashby, M.P.J. The Value of CCTV Surveillance Cameras as an Investigative Tool: An Empirical Analysis. Eur J Crim Policy Res 23, 441–459 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1007/s10610-017-9341-6

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-017-9341-6

Keywords

- Airtight-circuit television

- Surveillance camera

- Criminal investigation

- Policing

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10610-017-9341-6

Posted by: conanthowen1991.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Court Cases Involve Surveillance Cameras"

Post a Comment